Decades later, Finkel's details of Last Stand supported by archaeological evidence

April 9, 2020

-Submitted photo

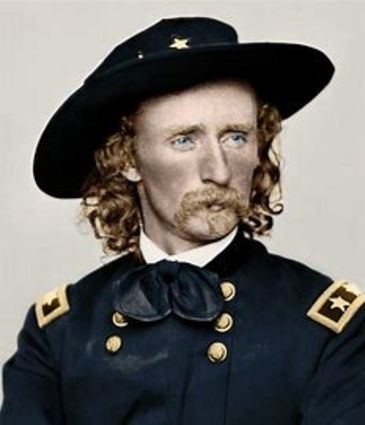

George Armstrong Custer was a Civil War hero whose battlefield exploits resulted in him reaching the rank of brevet (temporary) Major General. Custer was a Lt. Colonel at the time of Little Bighorn.

By Gary Lentz

Retired Ranger

Lewis and Clark Trail State Park

Special to the Dayton Chronicle

–Continued from the April 2, 2020, installment of Gary Lentz's informative program at the Blue Mountain Heritage Society's fundraiser in February.

Frank Finkel, after recuperating at a trapper's cabin for months, traveled to Fort Benton (in present-day Choteau County, Montana) where he reported in as a trooper from Co. C, Seventh Cavalry. Finkel was told he needed two witnesses and they're all dead. "Sounds like a government operation," Lentz opined.

It was the first he learned of the fate of his fellow soldiers. It was the first he had learned that they had been wiped out to a man.

Finkel had done his duty; the Army didn't believe him, and so he headed back down the Missouri River to where he enlisted...or so he says. Technically a deserter, he had few choices.

Because he was injured, and a veteran, there were some steamboat employees who helped him stow away. When the steamboat captain found out, he wanted to throw him off, but the sailors insisted he continue aboard, and he did.

One of the things that we [Lentz and Gordon Bateman] looked for was old steamboat captains' logs. We looked as hard as we could with various historical societies, similar to the Blue Mountain Heritage Society, in case one had been a repository for those kinds of records. If we could've found the log that had an entry from that period of time about a stowaway or an injured man, or something of that sort, it would've been a clincher of what he had been saying. But we haven't found that yet.

Frank worked and saved some money. He headed west. But this time he headed west as a civilian.

He eventually settles in Dayton and begins farming. No one is sure about his past; he just didn't talk about it much.

Finkel led a relatively quiet life socializing in Dayton affairs. He married a local girl, Delilah Ann Rainwater. He had a strong German accent, and seldom held long conversations with folks, but was well regarded.

For nearly 34 years, from 1878 until 1912, he hadn't mentioned his involvement with the Seventh Cavalry. Remember: Finkel told his wife "I was shot by an Indian."

But he didn't say where and how.

Then came that day when he decided to talk. Historian's questions were abundant: Is he telling the truth? Did Custer move over Nye-Cartwright Ridge? Did Custer fire volleys to attract the rest of his command? How did Custer deploy his troops? Did anyone see Frank Finkel's dilemma? Did Finkel have scars to validate his story? Did Finkel have enlistment papers? Was there anyone named Finkel at the battle? What did Finkel have to say about Custer?

Now this is interesting: If you were someone who plans to tell this story and make money on it, you have many opportunities to say, when somebody asked you a question, "Yes, yes, that's how it was."

Finkel didn't do that. He didn't really want this story told. He kind of fell into it and he was kind of stuck with it.

But he didn't lie about it. And this is what makes this story even more interesting.

For example, did Custer move over Nye-Cartwright Ridge? For many years, people thought he went down that Medicine Tail Coulee, and then retreated back up to Last Stand Hill. No one knew that he went down Medicine Tail Coulee, then went back up and around Nye-Cartwright Ridge to the Last Stand Hill, looking for a better position in which to attack the village.

Everyone thought he got to Medicine Tail Coulee, got hit by an Indian attack and went straight up over the hill. And it turns out that's not how it happened.

Before 1949, no one knew for sure. Then archaeologists discovered a hundred casings from the rifles used during the battle lying there on the ridge as if they had been fired there in a volley.

Finkel had said that's what they did, and he said it 37 years before the shell casings were discovered.

Now, interestingly enough, a hundred cartridges is two volleys for one company. Companies were supposed to have a hundred men in the Indian War period. Most companies had between 40 and 50 men, so, do the math and you find out there's either two companies firing one volley, or one company that fired two volleys, and they were probably doing just what Finkel said they had been doing: trying to attract attention, because the Indians hadn't come up from that direction.

The Indian response to the advance of Company C was rapid and overwhelming. They struck between the companies and effectively wiped out Company E, whose men were fighting dismounted. Company C retreated up the hill, formed a defensive line by shooting their horses to defend against the Indians' advance.

Historians have argued about that for generations. If that's true, where are the remains of Company C and Company E? Company C is scattered all over this battlefield, some here, some there, some all over the place.

Looking to discover–with accuracy–the remains of 28 men of Company E, archaeologists found, in a deep ravine, an arm sticking out of the hillside that nobody had seen until that point in time.

There had been a fire that had burned off the grass and when archaeologists went down and did some digging around, here was a shoulder and arm of a man.

They started doing some more work in that particular area and they found the remains of 28 men, right where Finkel said that they would be. Right where they had been killed.

And nobody, until that time, knew it. Finkel said it many years before anybody...to be accurate.

Did anyone report seeing a wounded man on a horse heading north? It turns out someone did.

Custer had blooded his horses by company, and this is important. What does it mean when you 'blood' your horses? You divide them up by color in your different companies.

Company E was the grey horse; Company C was sorrel roan; and so on.

Finkel was in Company C and he said he rode a sorrel roan.

Curley, an Indian scout, said he saw a man on a grey-colored horse, headed north, being pursued by some Indians. He didn't know what happened to him because the alkaline dust obscured his view.

When asked about what Curley had said, Frank Finkel said he rode a chestnut roan, he was in Company C, and was not riding a grey horse. It would've been a good way to validate his story, but Finkel stuck with what he knew.

-Submitted photo

Curley was a Crow scout with Lt. Col. George A. Custer's Seventh Cavalry, and is said to have witnessed a horseback trooper on a grey horse, headed north, pursued by some Indians.

And you know the irony in this? On that day, everybody rode a grey horse. The alkaline dust was so thick, it covered everything, including the men and the horses.

Custer may have blooded his horses, but in that battle, they were all grey horses.

And what Curley saw and said, was he saw somebody on a grey horse headed north.

And Finkel said, 'no, mine was a sorrel roan.' But he wasn't aware of what his horse looked like, because he was wiping blood out of his eyes.

Was Finkel's horse the one? We won't know for sure.

-To be continued